No Rattle; All Hum

Get behind the driver’s seat of a hybrid car, and start it up. The first thing you notice is how much quieter it is than a conventional car. If you are in a Toyota or Ford hybrid (and some GM hybrids), the internal combustion engine (ICE) gets cranked up, only to shut down again once it gets warmed up. This can happen quickly, or in colder weather, might take several minutes. At this point, the electric motor is now online, while the ICE remains dormant until needed.

Get behind the driver’s seat of a hybrid car, and start it up. The first thing you notice is how much quieter it is than a conventional car. If you are in a Toyota or Ford hybrid (and some GM hybrids), the internal combustion engine (ICE) gets cranked up, only to shut down again once it gets warmed up. This can happen quickly, or in colder weather, might take several minutes. At this point, the electric motor is now online, while the ICE remains dormant until needed.

The Toyota or Ford hybrid will stay in this all-electric mode until about 15 mph—or if you accelerate very slowly, all the way up to about 30 mph. At low speeds, the careful driver is effectively operating an electric car, with no gas being burned, and no exhaust spewed from the tailpipe. Pretty cool. The more spirited driver will cause the ICE to kick in at lower speeds.

Unlike the Toyota and Ford hybrids, the engines in Honda’s hybrids warm up but don't shut down completely until the first deceleration to a stop. This “auto stop” mode—conventional vehicles are wasting gas and spewing emissions during idle, while the hybrid is silent and gas-free—goes away when you lift your foot off the brake pedal, shift into gear, or depress the gas pedal.

Depending on how hard you step on the gas pedal, the car’s computer will determine how much power to draw from the ICE, and how much power to pull from the car’s electric motor. The dashboard shows you exactly when the electric “assist” is working. Each time the Honda hybrid driver moves forward and them comes to stop—unless the car is warming up or the air conditioning is cranked—the ICE shuts off completely. Once again, the car becomes eerily silent (unless you are cranking the tunes).

Get behind the driver’s seat of a hybrid car, and start it up. The first thing you notice is how much quieter it is than a conventional car. If you are in a Toyota or Ford hybrid (and some GM hybrids), the internal combustion engine (ICE) gets cranked up, only to shut down again once it gets warmed up. This can happen quickly, or in colder weather, might take several minutes. At this point, the electric motor is now online, while the ICE remains dormant until needed.

Get behind the driver’s seat of a hybrid car, and start it up. The first thing you notice is how much quieter it is than a conventional car. If you are in a Toyota or Ford hybrid (and some GM hybrids), the internal combustion engine (ICE) gets cranked up, only to shut down again once it gets warmed up. This can happen quickly, or in colder weather, might take several minutes. At this point, the electric motor is now online, while the ICE remains dormant until needed.The Toyota or Ford hybrid will stay in this all-electric mode until about 15 mph—or if you accelerate very slowly, all the way up to about 30 mph. At low speeds, the careful driver is effectively operating an electric car, with no gas being burned, and no exhaust spewed from the tailpipe. Pretty cool. The more spirited driver will cause the ICE to kick in at lower speeds.

Unlike the Toyota and Ford hybrids, the engines in Honda’s hybrids warm up but don't shut down completely until the first deceleration to a stop. This “auto stop” mode—conventional vehicles are wasting gas and spewing emissions during idle, while the hybrid is silent and gas-free—goes away when you lift your foot off the brake pedal, shift into gear, or depress the gas pedal.

Depending on how hard you step on the gas pedal, the car’s computer will determine how much power to draw from the ICE, and how much power to pull from the car’s electric motor. The dashboard shows you exactly when the electric “assist” is working. Each time the Honda hybrid driver moves forward and them comes to stop—unless the car is warming up or the air conditioning is cranked—the ICE shuts off completely. Once again, the car becomes eerily silent (unless you are cranking the tunes).

Digital Driveline

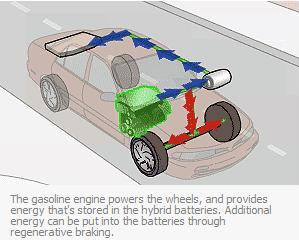

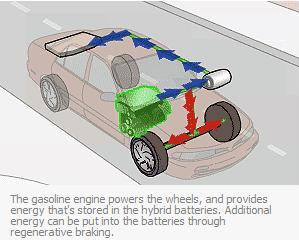

For your entire ride, the computer will be calculating when to let the gasoline engine do all the work and how much of a boost it needs from the electric motor. Because of the intermittent (but powerful) assist from the electric motor, the gasoline engine can achieve basically the same performance as a conventional car even when it has a smaller, more efficient size. Why put a high-horsepower, high-consumption engine into a car, when most drivers never drag race?

Meanwhile, back in the Toyota and Ford hybrids, when you step on the gas pedal, you are really controlling a pedal positioning device that tells the computer how fast you want to go, and the computer is once again making a lot of decisions about when to use the gas engine, when to go electric, or when to use a combination. The computer is, in fact, sending its signals to a gearbox, known as the power split device, which connects the gas engine and electric motors through a series of gears.

For your entire ride, the computer will be calculating when to let the gasoline engine do all the work and how much of a boost it needs from the electric motor. Because of the intermittent (but powerful) assist from the electric motor, the gasoline engine can achieve basically the same performance as a conventional car even when it has a smaller, more efficient size. Why put a high-horsepower, high-consumption engine into a car, when most drivers never drag race?

Meanwhile, back in the Toyota and Ford hybrids, when you step on the gas pedal, you are really controlling a pedal positioning device that tells the computer how fast you want to go, and the computer is once again making a lot of decisions about when to use the gas engine, when to go electric, or when to use a combination. The computer is, in fact, sending its signals to a gearbox, known as the power split device, which connects the gas engine and electric motors through a series of gears.

Battery Charge and Discharge

You probably understand the basics of how the gasoline engine is working, but where is the electric motor getting its juice? It’s actually drawing power from, or pumping power into, a set of nickel metal hydride batteries. The computer is performing a lot of magic by knowing when to reclaim excess energy when braking the wheels with the electric motor (which is now working like a generator). It also knows when to pass power from the battery to the electric motor for acceleration. The computer is monitoring the amount of charge in the batteries, making sure that they never charge more than 60 percent and never less than 40 percent of their capacity. In this way, automakers say, the batteries will last a couple hundred thousand miles.

You probably understand the basics of how the gasoline engine is working, but where is the electric motor getting its juice? It’s actually drawing power from, or pumping power into, a set of nickel metal hydride batteries. The computer is performing a lot of magic by knowing when to reclaim excess energy when braking the wheels with the electric motor (which is now working like a generator). It also knows when to pass power from the battery to the electric motor for acceleration. The computer is monitoring the amount of charge in the batteries, making sure that they never charge more than 60 percent and never less than 40 percent of their capacity. In this way, automakers say, the batteries will last a couple hundred thousand miles.

Wrap It All Up

Cover this technology with an aerodynamic frame and you’ve got yourself a major boost in fuel efficiency and a big-time reduction in poisonous, global-warming-causing tailpipe emissions. It’s not science fiction. It’s technology available today, in more than a dozen different sizes, shapes, and degrees of electric hybrid-ness.

Cover this technology with an aerodynamic frame and you’ve got yourself a major boost in fuel efficiency and a big-time reduction in poisonous, global-warming-causing tailpipe emissions. It’s not science fiction. It’s technology available today, in more than a dozen different sizes, shapes, and degrees of electric hybrid-ness.

No comments:

Post a Comment